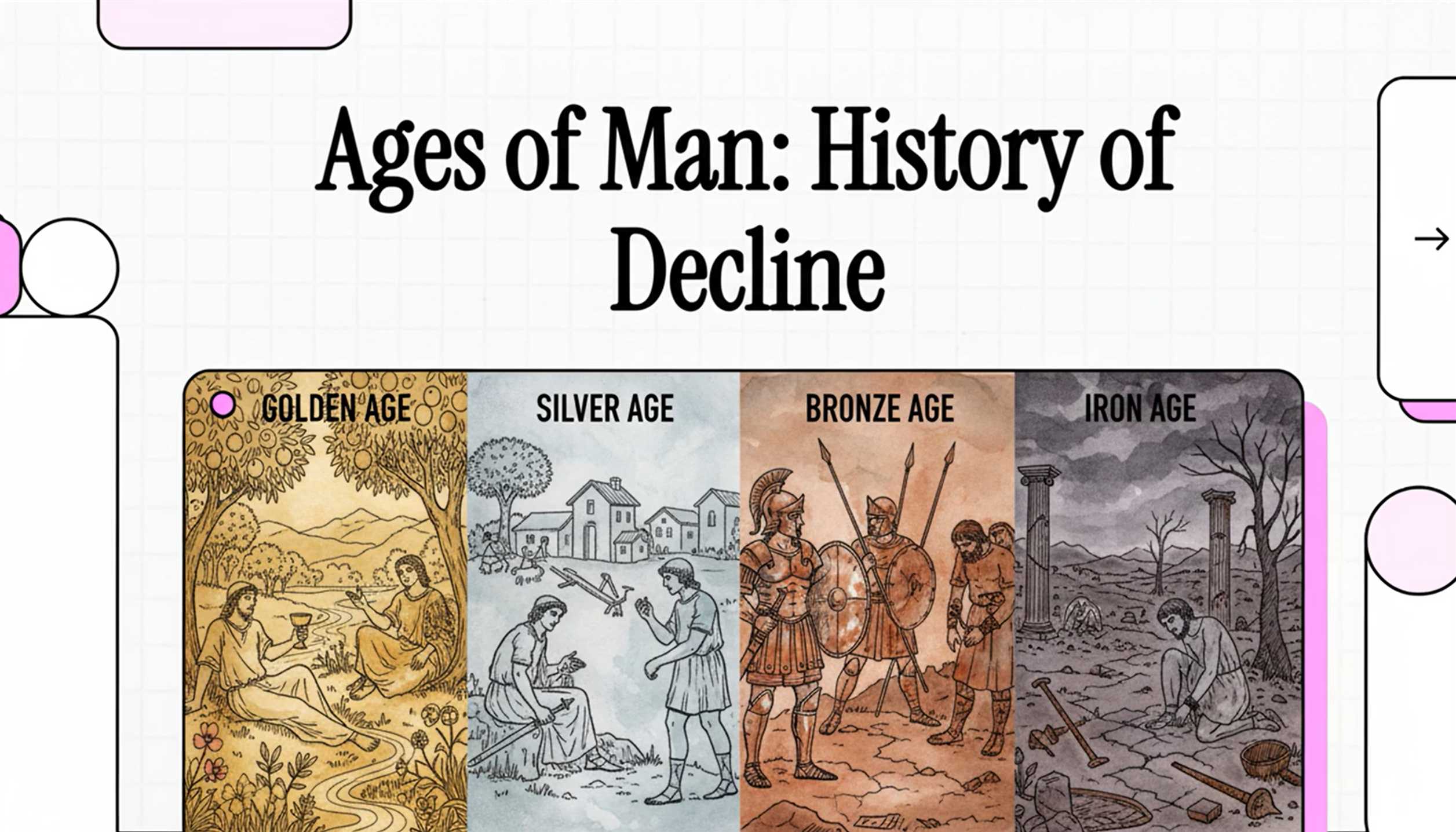

The Ages of Man - From the Glorious Golden Age to the Rusted Iron Age

The ancient Greek poet Hesiod described five ages of humanity. This article traces that grand mythological history, from the glorious Golden Age to the anguish-filled modern Iron Age.

The Ages of Man - From the Glorious Golden Age to the Rusted Iron Age

Is human history a story of progress or of decline? In his epic poem Works and Days, written around the 8th century BCE, the ancient Greek poet Hesiod described five ages through which humanity is said to have passed. It is a grand and pessimistic tale of decline, beginning with the glorious “Golden Age” and descending to the present “Iron Age.”

The Glorious Golden Age - A Life Among the Gods

The story begins with the “golden race,” the first created by the gods. They lived when the god Cronus ruled the heavens (Hesiod Works and Days 111). Their lives were like those of the gods, free from sorrow, hard labor, and the miseries of old age (Hesiod Works and Days 112–115). The Roman poet Ovid also depicted this era in his Metamorphoses, describing an eternal spring where Zephyrus, the west wind, gently caressed flowers that grew without being sown (Ovid Metamorphoses 1.107–108).

The earth brought forth grain without being tilled, rivers flowed with milk and nectar, and honey dripped from oak trees (Hesiod Works and Days 117–118; Ovid Metamorphoses 1.109–112). People needed neither laws nor punishments, for they upheld justice and trust of their own accord. They lived in peace, without war or weapons (Ovid Metamorphoses 1.89–100). Their death was like falling asleep, and afterward, they became holy spirits (daimones) who roamed the earth, watching over human affairs and guarding against injustice (Hesiod Works and Days 116, 121–126).

The later Neoplatonist philosopher Proclus interpreted this myth as an allegory for the state of the human soul. According to him, “gold,” by its nature of being incorruptible and rust-free, symbolizes a pure and undefiled intellectual life (Proclus In Platonis Rem Publicam Commentarii 2.75.15–18). The golden race becoming guardian spirits after death was thought to reflect their souls’ connection to the divine order (Proclus In Platonis Rem Publicam Commentarii 2.75.18–21).

Signs of Decline - The Silver Age

Next, the gods created a “silver race,” far inferior to the golden one in both body and mind (Hesiod Works and Days 127–129). The most distinct feature of this age was an unnaturally long childhood. A child would be raised by its mother for a hundred years, indulging in foolish play (Hesiod Works and Days 130–131). But when they finally reached adulthood, their lives were short and full of suffering. This was because they could not restrain their arrogant hubris toward one another and failed to honor the gods (Hesiod Works and Days 133–137).

According to Ovid, it was during this age that Jupiter (Zeus) ended the eternal spring, introducing the seasons of winter, summer, variable autumn, and a short spring (Ovid Metamorphoses 1.116–118). For the first time, people suffered from scorching heat and freezing ice, requiring shelter in caves and huts woven from branches (Ovid Metamorphoses 1.119–122). Angered by their impiety, Zeus hid this race beneath the earth. They came to be called the blessed spirits of the underworld, but they held only a second-rank status, inferior to the golden race (Hesiod Works and Days 138–142).

The Seeds of Violence - The Bronze Age

The third race Zeus created was the “bronze race.” Born from ash trees, they were terrible and strong, and completely unlike the silver race (Hesiod Works and Days 143–145). Their hearts were set only on the groaning-filled works of Ares—war—and on violent hubris. They did not eat grain and had hearts as stubborn as steel (Hesiod Works and Days 145–147).

As their name suggests, their weapons, homes, and tools were all made of bronze, for black iron did not yet exist (Hesiod Works and Days 150–151). Ovid also notes that this race was fiercer and quicker to take up savage arms, yet he adds that they were not yet completely wicked (Ovid Metamorphoses 1.125–127). Ultimately, however, they destroyed each other with their own hands and descended, nameless, to the cold house of Hades (Hesiod Works and Days 152–155).

A Fleeting Glory - The Heroic Age

In what seemed a continuous history of decline, Hesiod inserts an exceptional period. As the fourth race, Zeus created a “race of heroes,” who were more just and nobler (Hesiod Works and Days 157–158). They were of divine lineage and were also called demigods (Hesiod Works and Days 159–160). This was the era of the great wars of Greek mythology. These heroes fought in the war of the Seven against Thebes and in the great Trojan War over beautiful Helen (Hesiod Works and Days 161–165).

Though many of them perished in war, a special fate was reserved for some. Zeus settled them on the “Isles of the Blessed” at the ends of the earth (Hesiod Works and Days 167–168). There, the liberated god Cronus reigns as king, and the heroes live free from care, while the bountiful earth yields sweet fruit three times a year (Hesiod Works and Days 169, 172–173). The Heroic Age is not found in Ovid’s system, highlighting the depth of Hesiod’s unique mythological genealogy.

Anguish and Injustice - The Iron Age

Finally comes the fifth “Iron Age,” the era in which Hesiod himself lived. He laments, “I wish I had not been born among the fifth race of men. I wish I had died before or been born after” (Hesiod Works and Days 174–175). The people of the Iron Age are never free from toil and misery, day or night (Hesiod Works and Days 176–178).

But the defining characteristic of this age is a moral decay more severe than physical suffering. Father and son are not of one mind, guests do not respect their hosts, and even brothers are not as close as they once were (Hesiod Works and Days 182–184). Children dishonor their aging parents, might becomes right, and the wicked harm the good with false words and oaths (Hesiod Works and Days 185–194). Ovid, too, describes how modesty, truth, and faith fled, replaced by deceit, treachery, violence, and the lust for possession (Ovid Metamorphoses 1.128–131).

At last, the goddesses Aidos (Modesty) and Nemesis (Righteous Indignation), wrapping their beautiful forms in white robes, abandon humanity and depart for Olympus. Only painful sorrows are left on earth, and mortals have no defense against evil (Hesiod Works and Days 197–201). In Ovid’s account, the last of the celestials to leave the earth was Astraea, the goddess of justice (Ovid Metamorphoses 1.149–150).

Proclus saw this Iron Age as the lowest state of the soul, one dominated by passions (Proclus In Platonis Rem Publicam Commentarii 2.77.4–5). “Iron”—hard, dark, and earthly—symbolizes this state as a substance possessing little reason (Proclus In Platonis Rem Publicam Commentarii 2.77.6–10). The iron race is depicted as having only a faint glimmer of the light of reason, on the verge of degenerating into a completely bestial existence (Proclus In Platonis Rem Publicam Commentarii 2.77.11–14).

Hesiod also prophesies the end of this age: when people are born with gray hair and all moral laws are completely abandoned, Zeus will destroy this race as well (Hesiod Works and Days 180–181).

This story of the five ages is not merely a myth of the past. It is a timeless allegory showing how human society can collapse when justice is lost and violence reigns. Just as Hesiod implored his brother Perses to choose the path of “Justice” (Dike) over unjust “Violence” (Hubris), the story may be posing a moral choice to each of us, even in the darkest of times (Hesiod Works and Days 213–218).

(Editorial assistance by Yuki Suzuki)

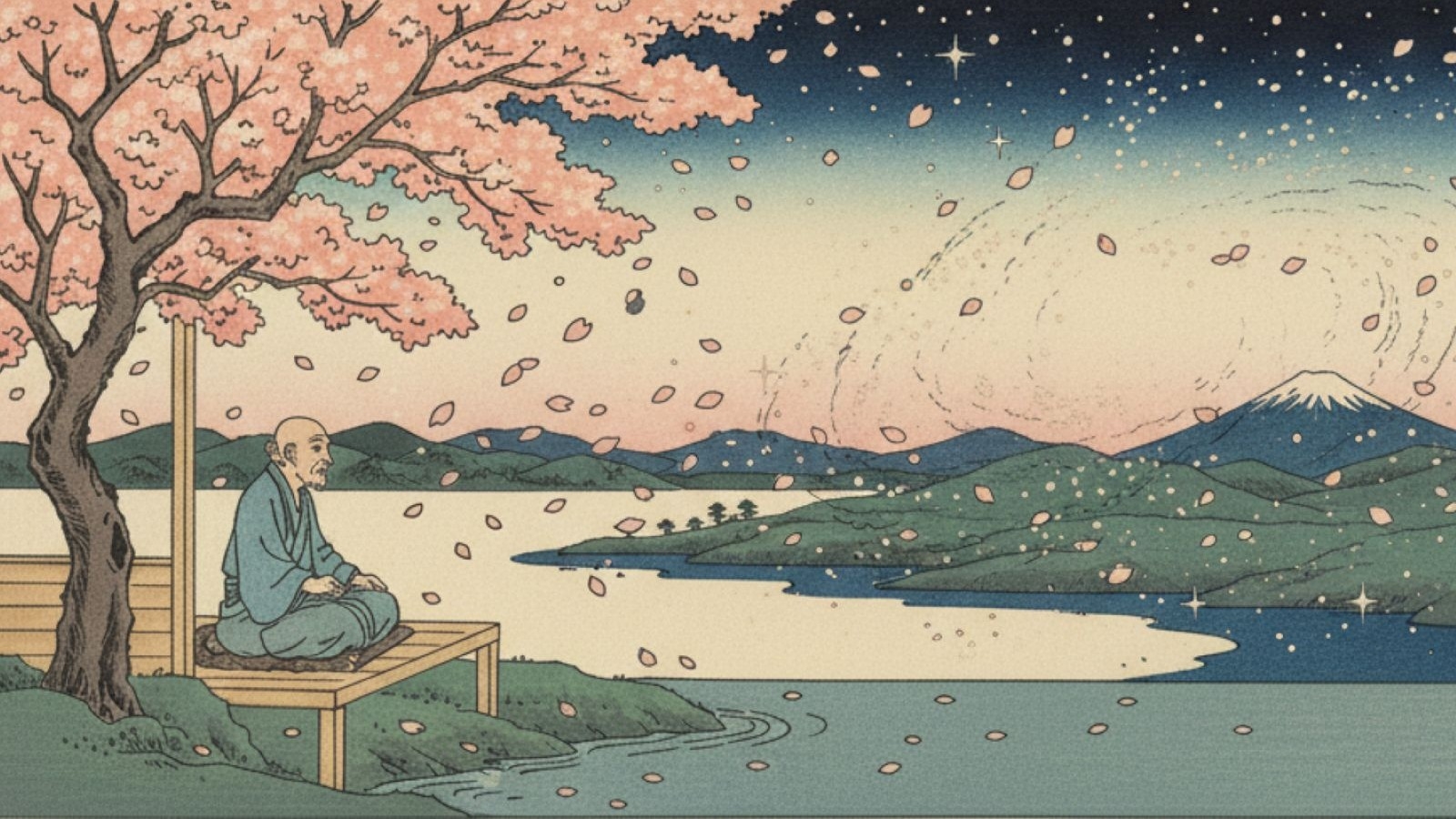

Japanese Views on Seasons - The Gaze of Literary Figures

Japanese literary figures have deeply engaged with the shifting seasons and the workings of life through various forms of expression such as novels and essays. Their delicate sensibilities and keen powers of observation open the door to a dialogue with nature for us, teaching us the beauty and philosophy hidden within everyday landscapes.

Japan's Primal Landscapes - A Tale of Memories Told by the Land

Superimposing the deceased onto the buzzing of flies, seeing gods in one-legged scarecrows. For Japanese people, these mysterious stories were not fantasy, but "life" itself, right next door. Longing for lands beyond the sea, legends remaining in ancient mounds. Why not travel through the frightening yet gentle "primal landscapes of the heart" gathered by Kunio Yanagita, Lafcadio Hearn, and others?

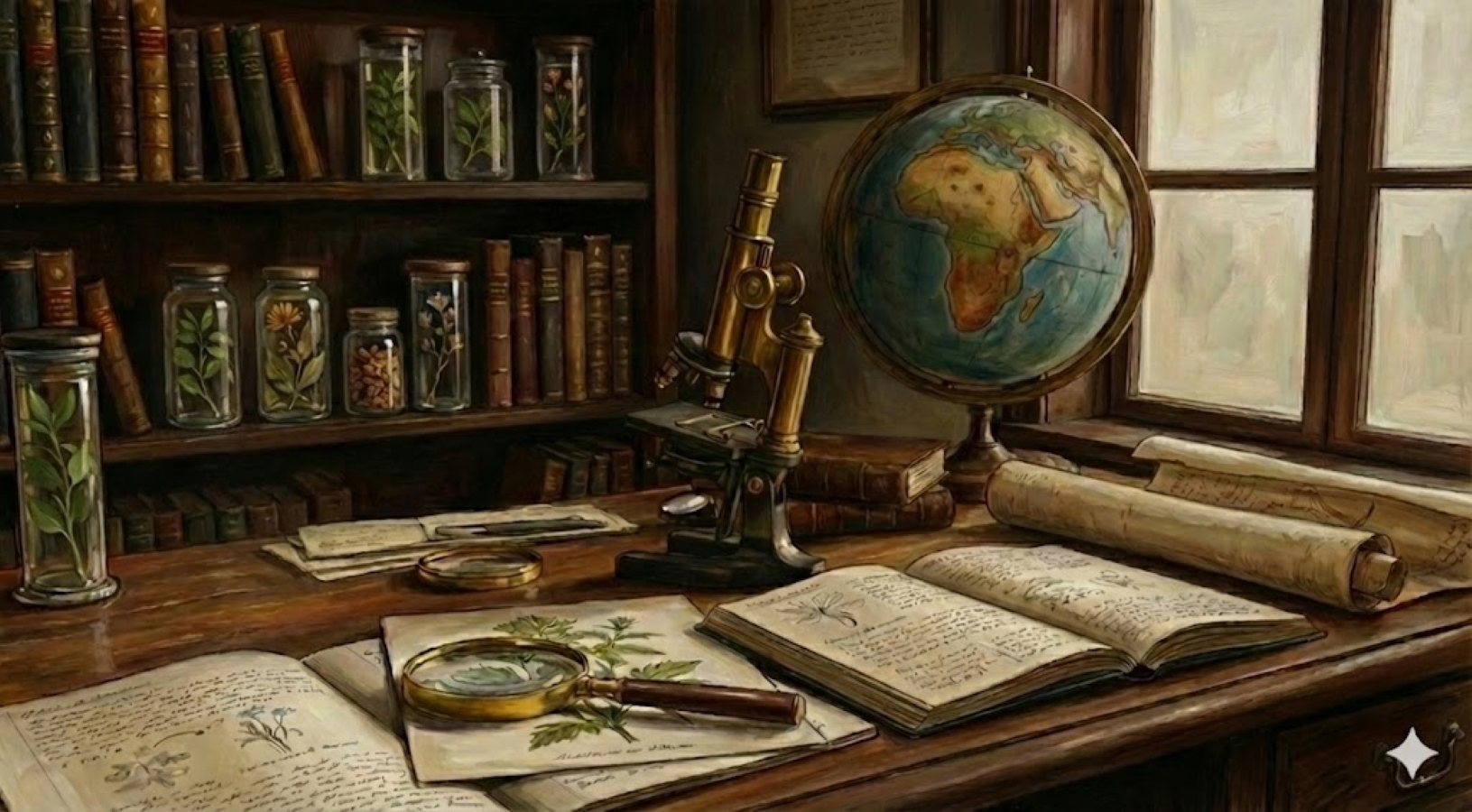

To Wonders Beyond Logic - The Beautiful Abyss Peered into by Scientists

Science is not just cold calculations. It is awe for nature beyond human understanding and an endless quest for beauty. Seeing the universe in a snowflake, feeling the ferocity of life in roadside grass... These are the adventurers of knowledge who confronted the overwhelming "mysteries" that appear only at the end of logic. We touch upon the records of their quiet yet passionate souls.

The Soul Screaming "I" - Stories of Fate and Pride by Modern Women

Should women's lives be plastered over with resignation to fate? Or is it a battle to break through social barriers and win one's own "life"? The dry self-mockery spat out by Ichiyō, the poignant scream released by Akiko for her beloved. We listen to the cries of their souls as they resisted the chains of their era, struggling through the mud to establish the "self."