Impermanence and Flow. Life's Truths as Seen by Kamo no Chōmei and Natsume Sōseki

Why do human hearts waver so? Kamo no Chōmei and Natsume Sōseki found the answer in the magnificent "flow" of nature. We invite you on a journey to explore universal insights that resonate with us across the ages.

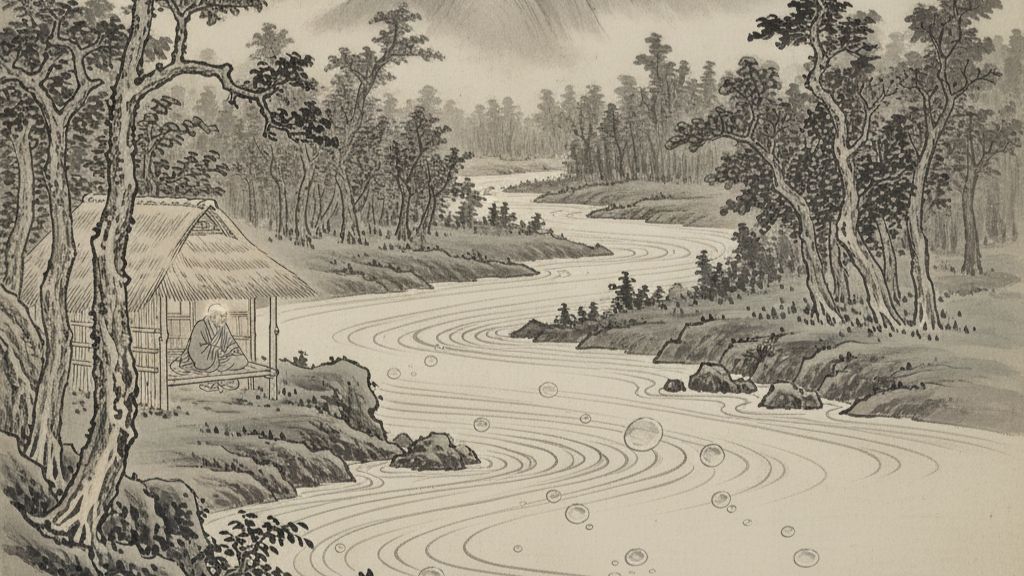

行く川のながれは絶えずして、しかも本の水にあらず。

The flow of the river is ceaseless, and yet the water is not the same.

— Kamo no Chōmei, Hōjōki

[Commentary]

If life were a river, what would the water flowing in it signify? This is the famously evocative opening line of Hōjōki, an essay that shines brilliantly in the history of Japanese literature. The author, Kamo no Chōmei, likens the state of all things in this world to the ever-changing flow of a river and the bubbles that form and vanish on its surface. The river’s current never ceases, yet the water within it is never the same from one moment to the next. This vivid metaphor masterfully depicts the truth of “mujō” (impermanence)—the idea that all things, from people to their dwellings, are in a perpetual cycle of creation and destruction. The resignation that nothing is certain and the deep insight that this very change is the law of the world are condensed into these few short words.

いづれの所をしめ、いかなるわざをしてか、しばしもこの身をやどし玉ゆらも心をなぐさむべき。

In what place can I settle, what deed can I perform, to lodge this body for but a moment and find some fleeting comfort for my heart?

— Kamo no Chōmei, Hōjōki

[Commentary]

Where in this world can one find a place of peace, even for a brief moment? This is the poignant question the author poses after listing the various afflictions of secular life—the gap between rich and poor, the constraints of human relationships, the terror of disasters. Chōmei laments that as long as one is bound by wealth and status, the soul can never truly be at rest, no matter where one lives or what work one does. These words can be said to highlight the transience of a life without anchor and the fundamental human craving for a place of peace. The question of what true tranquility is in a world where all is impermanent resonates in the reader’s heart, piercing through the ages.

どどんどどんと大きな濤が人の世を威嚇しに来る。

With a great thundering roar, massive waves come to menace the world of men.

— Natsume Sōseki, Kusamakura

[Commentary]

Is the sound of the crashing waves a lullaby, or is it a warning bell? This scene depicts the artist protagonist recalling a night spent at a dilapidated inn. From the inn, a vast ocean stretched out just beyond a grassy plain, and an eerie sound of waves echoed throughout the night. This powerful sentence, with its onomatopoeia, portrays the overwhelming force of nature and, in contrast, the smallness and fragility of the human world. The roar of the waves, seeming as if it could easily swallow up all human endeavors, symbolizes how fleeting a human life is before the inexorable flow of time and fate. It is a passage in which one can feel Sōseki’s unique view of impermanence, where the threat and beauty of nature intertwine.

喜びの深きとき憂いよいよ深く、楽みの大いなるほど苦しみも大きい。

The deeper the joy, the deeper the sorrow; the greater the pleasure, the greater the pain.

— Natsume Sōseki, Kusamakura

[Commentary]

Just as a bright light casts a dark shadow, life’s joys and sorrows are always intertwined. This is a line from the famous opening of the novel, where the protagonist, on an “inhuman” artistic journey, contemplates the difficulty of living in the human world while walking a mountain path. This beautiful parallelism captures the truth of life that opposing emotions—joy and sorrow, pleasure and pain—are, in fact, inextricably linked. If you try to cast one aside, you will lose the other as well. These words can be said to sharply depict the emptiness that lurks at the peak of happiness and the transience of the ever-changing human heart. The protagonist’s resignation, having reached this state of mind at the age of thirty, may lead readers to reflect on their own lives as well.

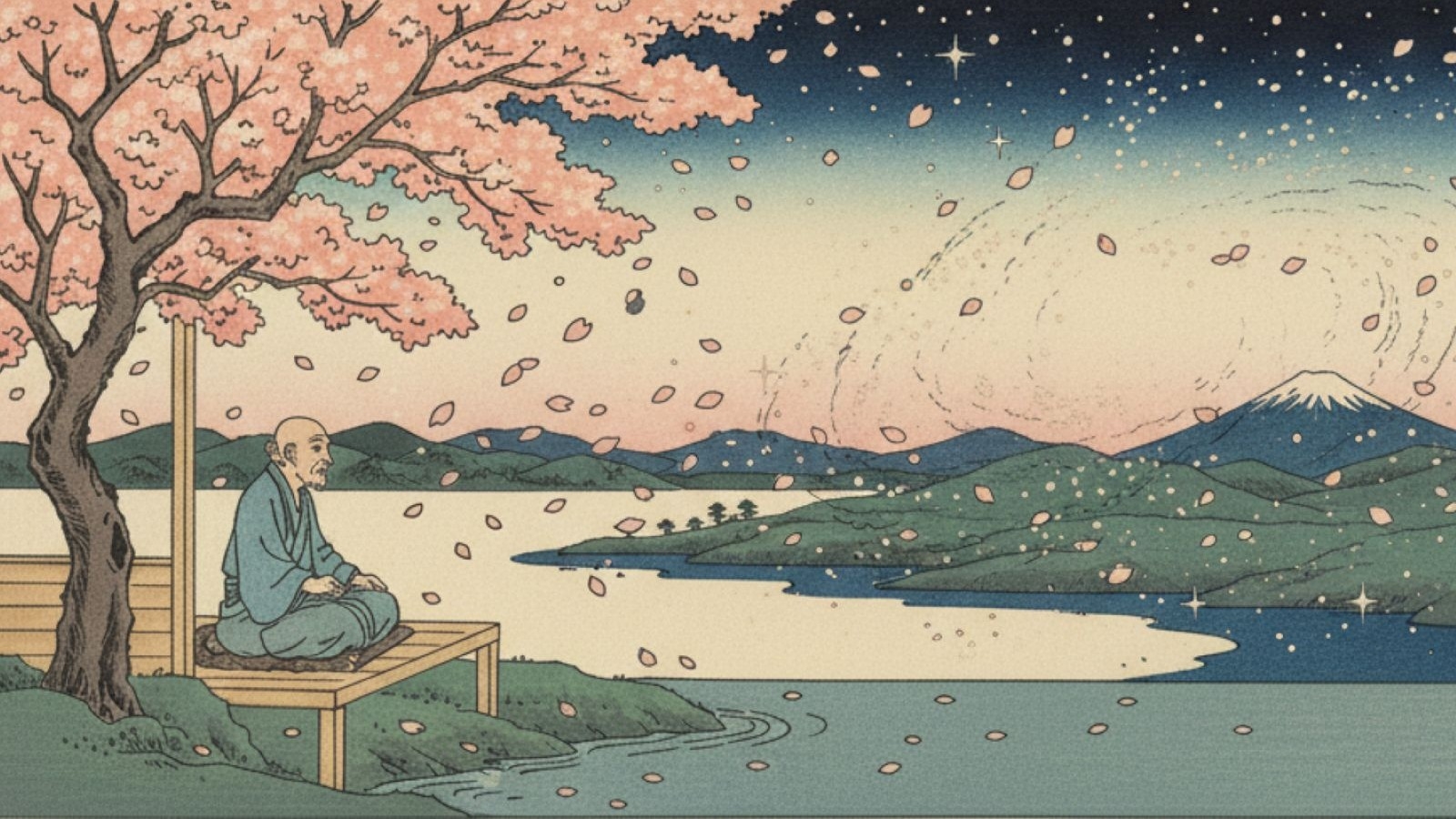

行末も知らず流れを下る。

Floating down the stream, not knowing the destination.

— Natsume Sōseki, Kusamakura

[Commentary]

Where is the small boat of our life heading? This is a scene from a dream the protagonist has. A woman is depicted floating down a river, singing in a beautiful voice, not asking for help but simply surrendering herself to fate. This short sentence is thought to symbolize the human condition, tossed about by a great power beyond one’s own will, an irresistible current of destiny. The image of being carried along, not knowing where one will end up, seems to be a direct reflection of the uncertainty and transience of life itself. This beautiful yet somewhat sorrowful dream image is a memorable scene that hints at the sense of impermanence that pervades the entire work.

自から来りて、自から去る、公平なる宇宙の意である。

To come of its own accord and to leave of its own accord—such is the impartial will of the universe.

— Natsume Sōseki, Kusamakura

[Commentary]

The blowing wind has no will; it simply passes through. Perhaps people are the same. This is a scene where the protagonist, in a quiet inn devoid of people, reflects while listening to the sound of the spring breeze. He finds the laws of the universe in the way the wind blows through the empty house. The spring wind does not blow for anyone’s sake, nor does it refuse anything; it simply appears and then departs according to natural law. This impartial and indifferent image of the wind seems to suggest that human life and death, encounters and partings, are also part of a larger flow that transcends individual will. Here lies a sense of resignation, a quiet acceptance of the irresistible principle of impermanence. It is a sentence that makes one feel deeply the transience of human existence within a grand cosmic view.

自然の経過がまた窮屈に眼の前に押し寄せて来るまでは、忘れている方が面倒がなくって好い

Until the course of nature once again presses uncomfortably before my eyes, it is better and less trouble to forget.

— Natsume Sōseki, The Gate

[Commentary]

How long can a person cover their ears to the footsteps of approaching destiny? Here, the state of mind of the protagonist, Sōsuke, who lives as if hiding from the world due to past guilt, is revealed. He consciously averts his eyes from pressing problems, trying to get through each day by feigning tranquility. This can be seen as a small resistance against the unchangeable flow of life, and also a kind of resignation. However, as the phrase “the course of nature” indicates, time will eventually pull him back to reality. His figure, indulging in a fleeting moment of ease, cannot help but evoke the fragility of a human being facing an unavoidable future.

父母未生以前本来の面目は何だか、それを一つ考えて見たら善かろう

What was your original face before your parents were born? It would be good to consider this.

— Natsume Sōseki, The Gate [The Zen Master]

[Commentary]

What were you before you were born? This is a kōan (a Zen riddle) given by a master to the protagonist, Sōsuke, who visited a Zen temple seeking salvation. He was hoping for liberation from his specific suffering, but what was presented to him was an immense and elusive question about his own origins. There is a great chasm between the practical problem of life’s anguish and the metaphysical question posed by Zen. However, it is this very question that serves as an opportunity to transcend the trivial self, tossed about by daily events, and to re-examine oneself within the larger flow of life. Sōsuke’s bewilderment is our own.

自然の進行がそこではたりと留まって、自分も御米もたちまち化石してしまったら、かえって苦はなかったろうと思った。

If the progression of nature had suddenly stopped there, and Oyone and I had instantly turned to fossils, I thought there would have been no suffering.

— Natsume Sōseki, The Gate

[Commentary]

If happy moments could last forever like fossils, would people be freed from suffering? This is a monologue from the protagonist, Sōsuke, as he recalls the peaceful days spent with his convalescing wife, Oyone, and a friend. This passage is nothing less than a poignant wish, born precisely because that happy time has passed. The merciless flow of life, where good times pass in a flash and a painful reality eventually arrives, is expressed in the words “the progression of nature.” The desire for time to stop at the peak of happiness reflects an attachment to things that change and a resignation to unavoidable change—in other words, the very transience of life itself. The brighter the glow of bygone days, the deeper the sense of stagnation in the present.

消えかかる過去は、夢同様に価の乏しい幻影に過ぎなかった。

The fading past was nothing more than a worthless illusion, much like a dream.

— Natsume Sōseki, The Gate

[Commentary]

Are bygone days the traces of a dream, or the shadow of an illusion? In his youth, Sōsuke was full of hope for the future and did not look back. To him, faded history and vanishing memories were equivalent to worthless illusions. This sentence contains both the strength of youth, which seeks to live only by looking forward, and at the same time, the peril of casting the past aside. However, as the story progresses, he himself becomes bound by this very past, which is none other than an “illusion.” The flow of time sharply pierces a transient aspect of life: that it creates not only hope for a brilliant future but also a past that will eventually become an illusion.

(Editorial Cooperation: Haruna Ishita, Momona Sassa)

Japanese Views on Seasons - The Gaze of Literary Figures

Japanese literary figures have deeply engaged with the shifting seasons and the workings of life through various forms of expression such as novels and essays. Their delicate sensibilities and keen powers of observation open the door to a dialogue with nature for us, teaching us the beauty and philosophy hidden within everyday landscapes.

Japan's Primal Landscapes - A Tale of Memories Told by the Land

Superimposing the deceased onto the buzzing of flies, seeing gods in one-legged scarecrows. For Japanese people, these mysterious stories were not fantasy, but "life" itself, right next door. Longing for lands beyond the sea, legends remaining in ancient mounds. Why not travel through the frightening yet gentle "primal landscapes of the heart" gathered by Kunio Yanagita, Lafcadio Hearn, and others?

To Wonders Beyond Logic - The Beautiful Abyss Peered into by Scientists

Science is not just cold calculations. It is awe for nature beyond human understanding and an endless quest for beauty. Seeing the universe in a snowflake, feeling the ferocity of life in roadside grass... These are the adventurers of knowledge who confronted the overwhelming "mysteries" that appear only at the end of logic. We touch upon the records of their quiet yet passionate souls.

The Soul Screaming "I" - Stories of Fate and Pride by Modern Women

Should women's lives be plastered over with resignation to fate? Or is it a battle to break through social barriers and win one's own "life"? The dry self-mockery spat out by Ichiyō, the poignant scream released by Akiko for her beloved. We listen to the cries of their souls as they resisted the chains of their era, struggling through the mud to establish the "self."